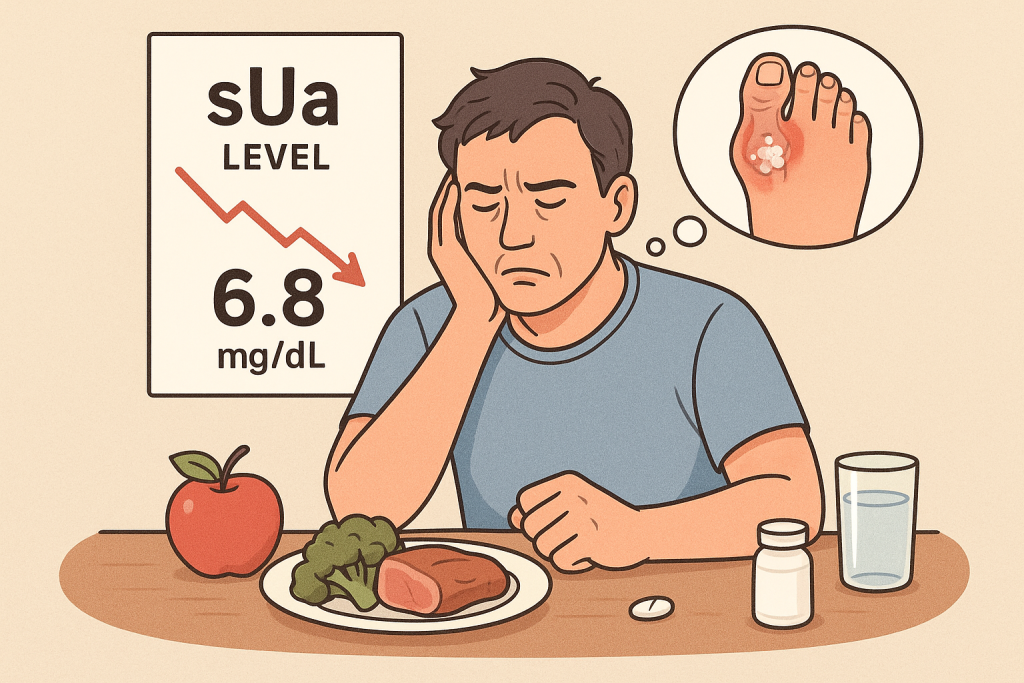

For the motivated patient managing gout, persistent hyperuricemia can be a source of immense frustration. You adhere to dietary restrictions, you take your medication, yet your laboratory results consistently show serum urate (sUa) levels that remain stubbornly above the therapeutic target. This clinical inertia is not just a number on a page; it represents an ongoing risk for debilitating inflammatory flares, the development of tophi, and progressive joint arthropathy.

The modern paradigm for gout management is a proactive, evidence-based “treat-to-target” (T2T) strategy. This approach, strongly advocated by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), is not about vague lifestyle advice but about achieving and maintaining a specific biochemical goal: a serum urate level of <6.0 mg/dL (360 µmol/L) to prevent crystal formation and dissolve existing deposits.

When this target remains elusive despite your best efforts, it is rarely due to a single, obvious cause. More often, the issue lies in a combination of subtle yet critical details. This article will explore three of the most common, evidence-based reasons for refractory hyperuricemia, providing a deeper understanding for patients and clinicians alike.

1. Suboptimal Urate-Lowering Therapy (ULT): The Critical Issues of Adherence and Titration

The most powerful tool in the management of gout is urate-lowering therapy (ULT), with xanthine oxidase inhibitors like allopurinol being the first-line agent. However, its real-world effectiveness is frequently compromised by two interconnected factors.

A. Non-Adherence to Medication

The single most significant barrier to achieving target sUa levels is medication non-adherence. A systematic review published in Rheumatology found that adherence rates to ULT are often alarmingly low, with some studies reporting that fewer than 50% of patients take their medication as prescribed one year after initiation (1).

The reasons for this are complex. During the long, symptom-free “intercritical” periods between flares, patients may feel well and perceive less need for a daily medication. This “out of sight, out of mind” phenomenon is dangerous, as the underlying hyperuricemia persists, allowing for the continued silent deposition of urate crystals. Sporadic adherence leads to fluctuating sUa levels, which not only prevents the dissolution of existing crystals but can paradoxically provoke new flares due to rapid shifts in urate concentration.

B. Failure of Dose Titration

Effective ULT is not a “one-size-fits-all” prescription. The ACR guidelines explicitly recommend a “start low, go slow” approach to allopurinol initiation (e.g., starting at 100 mg/day) to minimize risks. However, a crucial subsequent step is the titration of the dose every 2-5 weeks based on follow-up sUa measurements until the target of <6.0 mg/dL is achieved.

Unfortunately, a well-documented gap in clinical practice is the failure to properly titrate. Many patients are started on a low, introductory dose of allopurinol and are never re-evaluated or up-titrated, even when their sUa remains high (2). They are, in effect, being chronically underdosed.

Actionable Insight: The management of ULT is a dynamic partnership. Patients must commit to consistent daily adherence and actively engage with their physician, requesting follow-up sUa tests and discussing dose adjustments until the therapeutic target is met and maintained.

2. The Unrecognized Influence of Co-morbidities and Concomitant Medications

The human body is a complex system, and uric acid homeostasis is influenced by numerous factors beyond diet. Persistent hyperuricemia can often be traced to other health conditions or medications that are inadvertently “sabotaging” your efforts.

A. Diuretic Use

Thiazide diuretics (e.g., hydrochlorothiazide) and loop diuretics (e.g., furosemide) are commonly prescribed for hypertension and heart failure. However, they have a well-established hyperuricemic effect. These medications increase the reabsorption of urate in the proximal tubules of the kidneys, directly reducing its excretion and raising serum levels (3). For a patient on ULT, a diuretic can effectively work against their gout medication, necessitating a higher ULT dose or a change in their hypertension management.

B. Impaired Renal Function

Approximately 70% of daily uric acid disposal occurs via renal excretion. Therefore, any degree of chronic kidney disease (CKD) will inherently compromise the body’s ability to clear urate. The relationship is bidirectional and pernicious: uncontrolled hyperuricemia is an independent risk factor for the development and progression of CKD, and worsening CKD further exacerbates hyperuricemia (4). It is critical that your physician assesses your kidney function (e.g., via eGFR) and adjusts your gout management strategy accordingly.

C. Metabolic Syndrome and Insulin Resistance

Gout is strongly associated with metabolic syndrome. A key feature of this syndrome, insulin resistance, has been shown to reduce renal excretion of uric acid, contributing significantly to hyperuricemia independent of diet (5).

Actionable Insight: Maintain a complete and updated list of all your medications—including over-the-counter drugs like low-dose aspirin, which can also affect urate levels—and share it with your rheumatologist. Ensure all your co-existing health conditions are being considered as part of a unified gout management plan.

3. Hidden Dietary and Lifestyle Saboteurs Beyond Red Meat and Beer

Patients are often well-versed in the “classic” high-purine trigger foods. However, modern diets contain less obvious culprits that can significantly impact uric acid metabolism.

A. The Fructose Factor

Perhaps the most underestimated dietary driver of hyperuricemia is fructose. Unlike other sugars, fructose metabolism directly drives the production of purines. The rapid phosphorylation of fructose in the liver consumes adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is ultimately degraded into adenosine monophosphate (AMP), a direct purine precursor to uric acid (6).

This means that high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), found in countless sodas, juices, and processed foods, can raise uric acid levels as much as, or even more than, a high-purine meal. Large-scale epidemiological studies have confirmed a strong dose-dependent relationship between the intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and the risk of gout (7). The danger lies in its ubiquity; fructose hides in salad dressings, sauces, cereals, and countless other packaged goods.

B. Chronic Under-hydration

Adequate hydration is critical for renal function. When you are even mildly dehydrated, your blood volume decreases, which concentrates the solutes, including uric acid. Furthermore, dehydration can reduce the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), directly impairing the kidneys’ ability to filter and excrete waste products. Relying solely on diuretic beverages like coffee or tea without sufficient water intake can exacerbate this state.

C. Bridging the Gaps with Synergistic Support

Even with a meticulous approach, metabolic systems can benefit from targeted support. This is where a scientifically formulated nutraceutical strategy can play a valuable synergistic role. The philosophy at BISPIT is to provide precisely this kind of support. Our formulations are not a substitute for ULT, but a complementary component designed to help address these subtle but critical details.

By incorporating high-purity, natural extracts known to support the body’s endogenous metabolic pathways and renal excretory efficiency, BISPIT products are engineered to be a part of a comprehensive, proactive management plan. This approach helps create a more stable internal environment, supporting the consistent, day-to-day balance that is essential for keeping sUa levels safely below the therapeutic target.

Conclusion: A Call for a More Granular Approach

The frustration of persistently high uric acid is valid, but it is a solvable problem. The solution rarely lies in simply “trying harder” with the same strategy, but in taking a more granular, investigative approach. True control over gout is achieved through a meticulous partnership between an informed patient and an engaged clinician.

By systematically addressing the three key areas—optimizing ULT adherence and dosage, accounting for all co-morbidities and medications, and identifying hidden dietary saboteurs like fructose—you can uncover the root cause of refractory hyperuricemia. This detailed, multi-faceted strategy is the definitive path to finally achieving the target sUa level of <6.0 mg/dL and, with it, the long-term freedom from the devastating impact of gout.

References

- De Vera, M. A., Marcotte, G., Rai, S., Galo, J. S., & Bhole, V. (2018). Medication adherence in gout: a systematic review. Rheumatology, 57(9), 1551-1559.

- Doherty, M., Jansen, T. L., Nuki, G., et al. (2012). Gout: why is this curable disease so seldom cured? Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 71(11), 1765-1770.

- Choi, H. K., & Curhan, G. (2007). Diuretics and risk of incident gout in women: the Nurses’ Health Study. Hypertension, 49(2), 263-268.

- Johnson, R. J., Nakagawa, T., Jalal, D., et al. (2013). Uric acid and chronic kidney disease: which is chasing which? Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 28(9), 2221-2228.

- Choi, H. K., Ford, E. S., Li, C., & Curhan, G. (2008). Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with gout: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Care & Research, 59(11), 1599-1605.

- Nakagawa, T., Lanaspa, M. A., & Johnson, R. J. (2019). The effects of fructose on the kidney. Annual Review of Nutrition, 39, 221-243.

- Choi, H. K., & Curhan, G. (2008). Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ, 336(7639), 309-312.